The Ultimate Guide to Latin Verb Principal Parts

What are the four principal parts in Latin and why are they important? Read this ultimate guide to Latin verb principal parts to find out.

Principal parts come up all the time when you are learning Latin. Usually we use this term to refer specifically to the principal parts of verbs.

In this post, we will cover

- what the four principal parts are and why they are important

- how to get information from the principal parts

- how to find the principal parts of a Latin verb

- principal parts of defective, impersonal, and deponent verbs

If you are a beginning student, then the last section of the post may not be as important for you. So read just as far as seems relevant!

Why do Latin verb principal parts matter?

The function of principal parts is to give you all the information you need in order to identify and use the verb correctly. Grammarians have isolated the four forms of a verb that are most useful.

By useful, I mean the forms that give us all the necessary stems. The Latin principal parts cover the present active stem, the perfect active stem, and the perfect passive stem. This is all you need to identify any form of a regular verb.

We do the same thing in English. When you learn English as a second language, you are often given irregular (strong) verbs in three forms:

eat, ate, eaten

sing, sang, sung

throw, threw, thrown

If you memorize these forms, you know that you have to say “I eat”, “I ate”, and “I have eaten”. You have the forms you need to build every possible form of an English verb.

This is what we want to achieve with Latin principal parts.

And this is why it is crucial that you start memorizing verb principal parts as soon as possible. When you make a flashcard for a Latin verb, make sure you include all the principal parts.

In the beginning, you won’t know what to do with the 3rd and 4th principal parts. But trust me, it is much easier to memorize them as you go, rather than trying to go back and do it later.

(I always tell my students this, and they normally don’t listen. And then a month or so later they say, “Oh, I really wish I had taken your advice and memorized principal parts from the beginning!”)

Latin Principal Parts Around the World

Note that in this post, I am outlining the system of verb principal parts that appears in English-speaking countries. In some parts of the world, principal parts are a little different.

They still serve the same purpose: they help you to figure out the verb stems. But, for example, in some countries you will find only three principal parts (they skip the first one).

If this system of principal parts looks a little different than the one you are used to, don’t panic! Just focus on the names that I refer to the principal parts by – present infinitive, perfect passive participle, etc. – and you can still get a lot out of this post.

What are the four principal parts of a Latin verb?

Now that we have established the importance of memorizing principal parts, let’s start looking at them in more detail.

To begin with, here are the grammatical names for the four principal parts.

First Principal Part: 1st singular present indicative active

Second Principal Part: present infinitive active

Third Principal Part: 1st singular perfect indicative active

Fourth Principal Part: perfect participle passive (typically the masculine singular nominative)

If you have no idea what that means, don’t worry. We will go through everything step by step.

What information do Latin verb principal parts give you?

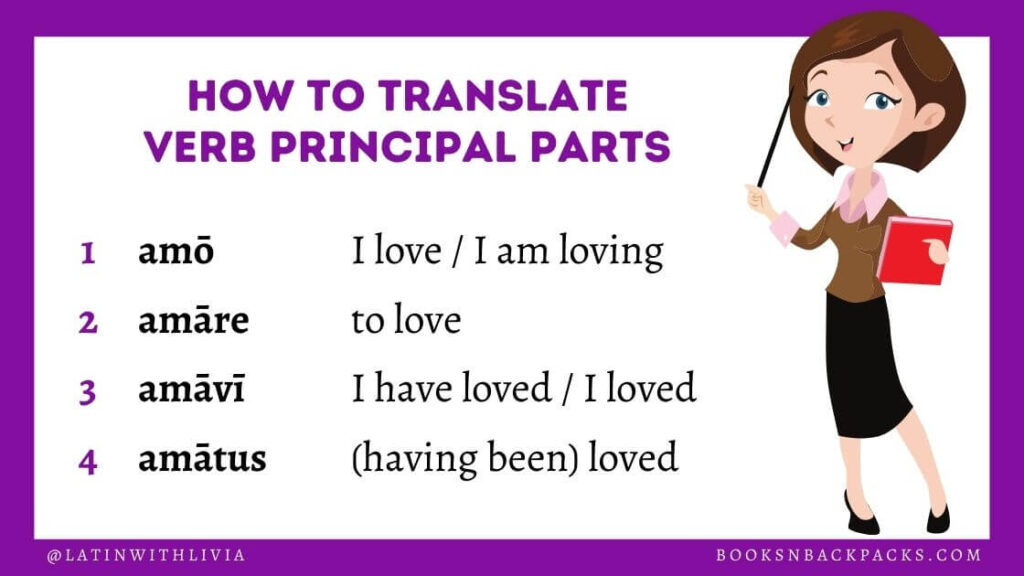

This section covers how to translate the individual principal parts and explains their uses.

First Principal Part

The first principal part is the basic form of a verb that you will see listed first in a dictionary or textbook. So it’s obviously important!

The first principal part is the 1st person singular present indicative active. This is a complicated way of saying that it is the “I” form of the present tense.

Here are some sample first principal parts with their translations. Notice that they all end in –ō. This is the 1st person singular ending.

- amō = I love / I am loving / I do love

- moneō = I warn / I am warning / I do warn

- mittō = I send / I am sending / I do send

- audiō = I hear / I am hearing / I do hear

If someone asks you, “How do you say ‘love’ in Latin?” you give the first principal part: amō. Technically it means “I love”, but we use it as the basic form of the verb.

Second Principal Part

The second principal part is the present active infinitive. In other words, you translate it as “to ________”.

The second principal part ends in –re, because this is the present infinitive active ending.

- amāre = to love

- monēre = to warn

- mittere = to send

- audīre = to hear

Knowing a verb’s second principal part is crucial for two reasons.

- You look at the second principal part to determine what conjugation a Latin verb belongs to. You can read more about the process in this post.

- The second principal part gives you the present stem of the verb. Remove the –re and voila! you have found the present stem. For example, the present stem of amō is amāre – re = amā-.

You use the present stem to build the present, imperfect, and future tenses (both active and passive). Very important!

Third Principal Part

The third principal part is the 1st person singular perfect indicative active. In simple lingo, it is the “I” form of the basic past tense.

Here are some examples. Note that they all end in –ī: this is the 1st person ending of the perfect tense.

- amāvī = I have loved / I loved

- monuī = I have warned / I warned

- mīsī = I have sent / I sent

- audīvī = I have heard / I heard

The third principal part is important because it gives us the perfect active stem. Remove the –ī to find this stem. For example, the perfect active stem of amō is amāvī – ī = amāv-.

You use this stem to build the perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect active tenses – as well as the perfect active infinitive.

Fourth Principal Part

The fourth principal part is the perfect participle passive, typically given in the masculine singular nominative.

In other words, you translate this principal part as “________ed” or “having been __________ed”.

- amātus = loved / having been loved

- monitus = warned / having been warned

- missus = sent / having been sent

- audītus = heard / having been heard

The fourth principal part – aka the perfect passive participle – serves three main purposes.

- The participle is used on its own as an adjective modifying nouns and pronouns.

- The participle is used with forms of sum (the verb “to be”) to create the perfect, pluperfect, and future passive tenses, as well as the perfect passive infinitive.

- When we remove the –us from the participle, we have the perfect passive stem. This stem is used to build future active participles. For example, the perfect passive stem of amō is amātus – us = amāt-.

If you are new to Latin, you may have no idea what all that means. And that’s okay. The important thing is to remember that all four principal parts are important for reasons that will become clear in the future.

Trust me. I’ve been studying Latin for 20 years at this point.

Alternate Fourth Principal Part

If you look at a Latin vocabulary list, you may notice that some verbs have a 4th principal part that ends in –ūrus, not –us. Examples:

- fugiō, fugere, fūgī, fugitūrus – “flee”

- sedeō, sedēre, sēdī, sessūrus – “sit”

- sum, esse, fuī, futūrus – “be; exist”

What is happening here? Well, let’s think about this logically. The fourth principal part in –us is a perfect passive participle meaning “having been blank-ed”.

But some verbs can’t be used in the passive. We can’t say “I have been fled” or “I have been existed”. It doesn’t make sense.

For these verbs, the 4th principal part is the future active participle (typically in the masculine nominative singular form). The future active participle ends in –ūrus and is translated as “about to blank“.

- fugitūrus = about to flee / going to flee

- sessūrus = about to sit / going to sit

- futūrus = about to be / going to be

And there you go. Now you know why some 4th principal parts end in –us and some in –ūrus.

And now you know how to translate the principal parts of a Latin verb. You also have an idea of what you do with those principal parts. So it’s time to move on to finding a verb’s principal parts.

How do you find the principal parts of a Latin verb?

There is one foolproof way of finding any Latin verb’s principal parts: look them up in a dictionary or textbook. For obvious reasons, though, you don’t always want to be referencing your dictionary.

So in this section, we will talk about principal part patterns and what you can expect to see.

Luckily, the first two principal parts of each conjugation are always regular. So that’s two less forms to stress over. Memorize the endings once, and you have memorized them for all the verbs of that conjugation.

The 3rd and 4th principal parts cause more issues. For some Latin verbs, especially those of the 3rd conjugation, you simply have to look up the last two principal parts. For other verbs, there is a specific pattern.

But you have to know that specific pattern – and you also need to know which verbs follow it. That’s where memorization comes in.

We will go through each conjugation one by one. But first, if Latin verb conjugations confuse you a bit, go read this post on how to find the conjugation of any Latin verb.

Principal Parts of the First Conjugation

Most 1st conjugation verbs have predictable principal parts. The endings of the principal parts are as follows:

1PP: -ō

2PP: -āre

3PP: -āvī

4PP: -ātus

Sample verbs:

- amō, amāre, amāvī, amātus – “love”

- clāmō, clāmāre, clāmāvī, clāmātus – “shout”

When you see something like “amō, 1” written in a dictionary, it means that the verb has standard 1st conjugation principal parts.

Some 1st conjugation verbs have irregular 3rd and 4th principal parts, and these you simply have to memorize.

Principal Parts of the Second Conjugation

Just like with the 1st conjugation, many 2nd conjugation verbs follow a pattern in their principal parts.

1PP: -eō

2PP: -ēre

3PP: -uī

4PP: -itus

Sample verbs:

- moneō, monēre, monuī, monitus – “warn, advise”

- terreō, terrēre, terruī, territus – “terrify, scare”

If a verb conforms to this pattern, you will often see its principal parts listed in abbreviated form: “moneō, 2”. Other 2nd conjugation verbs have non-standard 3rd and 4th principal parts.

Principal Parts of the Third Conjugation

3rd conjugation verbs are the absolute worst when it comes to principal parts. We can only say for certain what the endings of the first two principal parts are.

1PP: -ō / iō

2PP: -ere

The 3rd and 4th principal parts vary drastically. You really do just have to memorize them. Here are a few sample verbs:

- mittō, mittere, mīsī, missus – “send”

- pellō, pellere, pepulī, pulsus – “push”

Note that the 3rd principal part will always end in –ī, and the 4th principal part in –us. It’s the stem that comes before these endings that we cannot predict.

Principal Parts of the Fourth Conjugation

There is a standard pattern for 4th conjugation principal parts.

1PP: -iō

2PP: -īre

3PP: -īvī

4PP: -ītus

Sample verbs:

- audiō, audīre, audīvī, audītus – “hear”

- serviō, servīre, servīvī, servītus – “serve, be a servant to”

If a 4th conjugation verb has regular principal parts, you will typically see it listed in the following fashion: “audiō, 4”. But there are many 4th conjugation verbs that do not follow this pattern.

Irregular Latin Verb Principal Parts

As I have noted above, not all Latin verbs have easily predictable principal parts. Sometimes the 3rd and 4th principal parts look so different that you can’t even tell they belong to the same verb as the 1st and 2nd principal parts.

(For example, this is the case with the extremely common Latin verb sum, which means “be.” The similarly common verb possum also has an unexpected principal part.)

In such instances, I highly recommend that you memorize the principal parts. At bare minimum, be able to recognize them on sight. You will thank yourself later!

Even the most confusing principal parts generally have some sort of logic to them. The problem is that it is often hard for beginning students to make the connection.

So I have created a download to help you memorize irregular principal parts. The download has two things inside:

- A list of 20+ verbs whose principal parts you should definitely know

- Tips for memorizing the principal parts of each verb

Sign up for my Latin newsletter to get this download . . . and all future Latin study guides.

How are you feeling about principal parts? Hopefully you understand things a bit better now.

If you are a new student, then you will probably want to stop right here. The last section of this article deals with atypical principal parts. If you’re more advanced, take a deep breath and keep reading.

Atypical Principal Parts

Some verbs have different-looking principal parts for various reasons. In this section, we will cover defective verbs, impersonal verbs, and deponent verbs.

Defective Verbs

Some verbs are defective – that is, they can only be used in certain tenses. As a result, they are missing certain principal parts.

For instance, the verb coepī almost always appears in the perfect system (perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect tenses). Because of this, it only has two common principal parts (3rd and 4th):

- —, —, coepī, coeptus – “begin”

Other verbs only appear in the present system (present, imperfect, and future tenses). These verbs also have just two principal parts: 1st and 2nd.

- feriō, ferīre, —, — – “strike, smite”

- maereō, maerēre, —, — – “be sad”

The verbs were likely complete at some point, but over time certain forms went out of use. So don’t be surprised if you come across a verb that lacks the full set of principal parts.

Impersonal Verbs

Some verbs can only be used impersonally. This means that they cannot take a personal subject. In English, such verbs have “it” as their filler subject. In Latin, we simply put these verbs in the 3rd person singular.

Since Latin impersonal verbs can only be used in the 3rd person singular, their principal parts look a bit different. Instead of using 1st person forms in the 1st and 3rd principal parts, we use 3rd person forms.

Sample impersonal verbs:

- decet, decēre, decuit – “it is suitable / proper / becoming”

- libet, libēre, libuit, libitum est – “it pleases / it is pleasing”

- licet, licēre, licuit, licitum est – “it is permitted / allowed”

Deponent Verbs

The last subject we need to discuss in this post is the principal parts of deponent verbs.

Deponent verbs are passive in form, but active in meaning. This means that their principal parts are passive forms, not active ones – so their standard patterns are different.

Furthermore, deponent verbs only have three principal parts. Why? Because the 3rd and 4th principal parts of a regular verb reflect the active and passive perfect stems, respectively. Since deponent verbs can only be passive in form, there cannot be two different perfect principal parts.

Here are the standard endings of the principal parts of deponent verbs:

First Conjugation: -or, -ārī, ātus sum

Second Conjugation: -eor, -ērī, itus sum

Third Conjugation: -or / ior, -ī, ??

Fourth Conjugation: -ior, īrī, ītus sum

The principal parts are, however, translated into English in the same way as regular principal parts are. This is because deponent verbs are active in meaning.

Final Tips for Latin Verb Principal Parts

Wow. That was a long post. Congratulations if you made it all the way through. Definitely bookmark this page to come back to – it’s a lot of information to process all at once.

As I have already said multiple times, I highly recommend that you get in the habit of memorizing principal parts as you go. If you are serious about Latin, they are an absolute must.

But if you haven’t been memorizing your principal parts, then definitely download my handy list of 20+ Latin verbs whose principal parts you should absolutely know.

YOU MAY ALSO LOVE:

The Ultimate Guide To Latin Person & Number

Digital vs. Paper Flashcards: Which is Best?

How To Review Flashcards Effectively

Hello! Thank you for all of this helpful information! Question: What are the four principal parts of the verb “administro”?

Thank you again!

Hi Nichole, “administrō” is a regular 1st conjugation verb, so the principal parts are “administrō, administrāre, administrāvī, administrātus.” I hope this helps!

Can you speak to why the verb Timeo, timere, timui does not have a 4th principle part?

Hi Erika, this is a great question. The 4th principal part is the perfect passive participle, and for whatever reason *timeō* does not have a perfect passive participle – or at least, the form does not survive in any Latin texts.

Usually verbs lack a 4th principal part when they can’t be used in the passive voice at all. In the case of *timeō*, it DOES have some passive forms, just not in the perfect system. There is not a very satisfactory answer as to WHY – it’s simply a quirk of how this verb is used in Latin.

Hi Livia

The 4th principal part of a Latin verb is named by you and others as “the perfect participle passive”. Being as I have some lack of familiarity as yet with the fine points of English verb tenses, and my aged (1953) Latin textbook doesn’t use that description, I’m in a bit of a muddle. My difficulty is in trying to figure out in which tense to find “the perfect participle passive”. Is it in the Perfect Indicative (Perfect Tense) which represents an action as completed in present time, or as simple past, or is it in the Future Perfect Indicative (Future Perfect Tense) which represents an action as completed in some future time? I can’t yet make out all those haves and shall haves, etc.

Hi Marian, good question. Participles are *verbal adjectives* and therefore they do not have a person or mood like standard conjugated verbs. This is why you will not find them listed in conjugation charts. They usually receive their own section in a textbook.

The perfect participle passive belongs to the perfect tense, which means that it is the participial equivalent of the perfect indicative passive. E.g.

Perfect indicative passive: *puella laudāta est* = “the girl has been praised”

Perfect participle passive: *puella laudāta rīdet* = “the girl, having been praised, laughs”

I hope that this helps to answer your question. I will add participles to my list of future posts!

Why are some 4th principal parts shown in brackets?

Hi Kathy, I don’t think I have used any brackets in this post, so I am not quite sure what you are referring to. Sometimes textbooks will use parentheses or brackets to indicate that a 4th principal part is rarely used, but I would need to see the specific instance to be sure.