The Ultimate Guide to the Latin Genitive Case

The genitive case is extremely important in Latin. This ultimate guide will tell you what the genitive is, how to translate it, and how to use it.

This post is relevant to students of all different levels, from beginning to advanced. Information is presented from most important to least.

If you are just embarking on your Latin journey, you may only be interested in the beginning of the post. But if you are an advanced student, you will want to read to the end!

Now that we have that out of the way, let’s get started.

This post may contain affiliate links and I may receive a commission, at no extra cost to you, if you make a purchase through a link. See my disclosures for more details.

Latin Genitive Case: The Basics

The genitive case is the case of possession, origin, and source. Typically, you can translate a noun in the genitive as “[blank]’s” or “of [blank]”. Your translation may be very literal, but it will work.

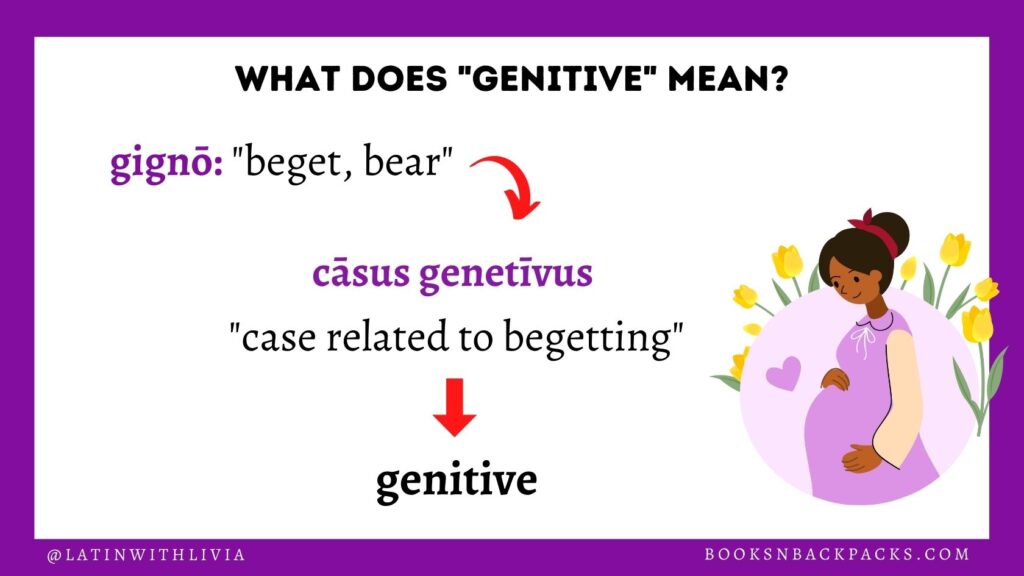

The etymology of the genitive case hints at its use. “Genitive” comes from the Latin cāsus genetīvus “case related to begetting”, which in turn comes from the verb gignō “beget, bear, produce”. So the genitive is literally the “begetting” or the “producing” case.

The English word “generate” comes from the same root. If you associate genitive with generate, this can help you to remember that the genitive case is associated with where something comes from or who possesses it.

In the next section of this post, I will give you lots of examples of the genitive case in action. But first, there is another matter we need to address.

The genitive case is extremely important for Latin learners. Why? Because we look to a noun’s genitive singular to determine its declension as well as to find its base.

For this reason, dictionaries and textbooks will give you both the nominative singular and the genitive singular of each noun. If you don’t know a noun’s genitive singular, you won’t know its declension or its base. And as a result, you will not be able to figure out how the noun fits into its sentence.

When you are studying Latin vocabulary, definitely memorize the genitive along with the nominative. For instance, if you create flashcards, be sure to include the genitive!

Now that we have established why the genitive is important for students, it’s time to dive into the nitty-gritty details of translation.

Uses of the Genitive Case in Latin

There are many uses of the genitive case in Latin. In this post, I list the ones most relevant to a Latin student – in rough order of importance.

Possessive Genitive

The fundamental use of the genitive in Latin is to indicate possession. In English, we show possession by adding ‘s (apostrophe + S) or a simple apostrophe to a noun. A second option is to say “of [blank]”.

In Latin, you don’t need any extra words or signs. You just need to put the possessor in the genitive!

Here are some examples of possessive genitives (indicated in bold):

casa agricolae = the farmer’s house / the house of the farmer

dōna amīcōrum = the friends’ gifts / the gifts of the friends

lūcem sōlis videō. = I see the light of the sun / the sun’s light.

In casā amīcōrum agricolae sumus. = We are in the house of the friends of the farmer.

Possessive genitives usually come immediately after or before the noun they depend on. As the last example demonstrates, you can have strings of possessive genitives, just like in English.

Partitive Genitive or Genitive “of the Whole”

This genitive has a complicated-sounding name, but in actuality the use is quite simple. If you are talking about part of a whole or a member of a group, the whole or the group is put in the genitive. (This is why it is called the genitive “of the whole”!)

We also use the partitive genitive to describe groups of people or of things. In this context, the people or the things are in the genitive.

Examples:

pars fābulae = part of the story (= part of a whole)

plūs pecūniae = more (of) money (= part of a whole)

nēmō fēminārum = no one / none of the women (member of a group)

minor sorōrum = the younger of the sisters (member of a group)

turba nautārum = a crowd of sailors (a group of people)

manus mīlitum = a group of soldiers (a group of people)

mīlia passuum = thousands of paces (a group of things)

These examples should give you an idea of the kinds of circumstances in which the partitive genitive appears. The partitive genitive can come after nouns, adjectives, pronouns, numerals, and even adverbs.

If you are interested in reading more about the partitive genitive, I recommend §346 of Allen and Greenough’s New Latin Grammar (more about this resource below).

One last thing: there is an easy trick for telling apart the possessive and the partitive genitives. Try translating the phrase with the English apostrophe + S construction. If it makes sense and has the same meaning, the genitive is possessive.

Take, for example, the phrase turba nautārum, which I have translated above as “a crowd of sailors”. If I turn that into “the sailors’ crowd”, it doesn’t really make sense. At the very least, “a crowd of sailors” and “the sailors’ crowd” mean different things.

This is a sign that you are dealing with a partitive genitive, not a possessive.

Objective Genitive and Subjective Genitive

The objective genitive turns up quite frequently, so it is important to discuss. I have included the subjective genitive here, as well, because it is easiest to explain the two uses together.

Objective Genitive

Let’s start by looking at a Latin sentence.

Puerī nautam timent. = The boys fear the sailor.

In this sentence, the boys are the subject. They are performing the action of fearing. The sailor, on the other hand, is the direct object. He is receiving the action of fearing.

If we wanted to talk about this fear as a noun, we could use an objective genitive and say

timor nautae = fear of the sailor

This isn’t a possessive genitive, because we aren’t talking about the sailor‘s fear. Remember, it is the boys who fear the sailor, not the other way around.

The sailor is the object of the boys’ fear – and so nautae is an objective genitive.

Here are a few more examples of objective genitives:

amor matris = love of his mother (= the man loves his mother)

imperium turbae = command of/over the crowd (= the king commands the crowd)

memoria impetūs = memory of the attack (= the soldiers remember the attack)

In order for a noun to be able to take an objective genitive, the noun needs to have some sort of verbal force. In other words, the noun needs to express an action.

Memory is the action of remembering, command is the action of commanding, etc. That’s why memoria and imperium can be followed by objective genitives.

Subjective Genitive

Now it is time to return to our original sentence and see what a subjective genitive is.

Puerī nautam timent. = The boys fear the sailor.

This time, instead of focusing on the sailor, let’s describe the fear with relation to the boys.

timor puerōrum = the boys’ fear

Puerōrum is a subjective genitive. Why? Because the boys are the subject of the action of fearing. They are the ones performing the fearing.

Here are more examples of subjective genitives:

amor matris = a mother’s love / love of a mother (= the mother loves her son)

imperium rēgis = the king’s command (= the king commands the crowd)

memoria uxoris = the wife’s memory / the memory of the wife (= the wife remembers the attack)

In all of these examples, the genitive refers to the subject of the action. And that’s why they are subjective, not objective, genitives.

Now you may ask: what is the difference between a subjective genitive and a possessive genitive? If you say “the wife’s memory”, doesn’t the memory belong to her? And doesn’t that make it possessive?

This is a valid point, and this is why I don’t like to focus on the subjective genitive very much. It is a sub-category of the possessive genitive and for the average student, it doesn’t make any difference whether you think of it as possessive or subjective.

Then why am I bringing it up? Two reasons.

First, the subjective genitive is the flip side of the objective genitive, and the objective genitive is important. And second, grammar books and textbooks often refer to the subjective genitive, so I want to mention it here.

Objective vs. Subjective Genitive

Before we move on, I want to address one last potential issue: how do you tell whether a genitive is objective or subjective?

If you see the expression amor matris (love of the mother), how do you know what the mother’s relation to the love is? Is the mother the one who loves someone (subjective genitive)? Or is the mother being loved by someone (objective genitive)?

I don’t have a satisfying answer to give you. Basically, you need to rely on context. Is the passage in question about a mother sacrificing herself for her son? Well, then, amor matris refers to the mother’s love – and thus matris is a subjective genitive.

But if the passage is about a son sacrificing himself for his mother, then amor matris refers to the son’s love for his mother – and thus matris is an objective genitive.

Predicate Genitive or Genitive of Characteristic

This genitive receives different names in different grammar books. But fortunately the concept is straightforward, even if people can’t agree upon what to call it. This genitive always appears along with an infinitive and a form of the verb sum (to be).

A few examples should clear things up.

nautae est nāvigāre = to sail is (characteristic) of a sailor

stultī erat impudenter loquī = to speak shamelessly was (characteristic) of a fool

mōris eius populī est sub Iove dormīre = it is (of) the custom of that people to sleep under the open sky

pugnāre nōn est puerōrum = it is not (the job) of boys to fight

As you can see from these examples, the genitive expresses for whom a certain action is characteristic. This is why it has earned the name “genitive of characteristic”. From a grammatical perspective, the genitive is the predicate of the verb sum, which is why it can be called a predicate genitive.

Technically, this genitive is a sub-category of the possessive genitive. But I have listed it separately because it looks very distinct and it often confuses students.

Genitive of Description or Quality

The genitive of description or quality is, logically, used to describe a quality of a person or thing. For example:

vir magnae virtūtis = a man of great courage

puella tantae sapientiae = a girl of such wisdom

liber eius modī = a book of that kind

The important thing to remember here is that you will only see the genitive of quality if the genitive noun is modified by an adjective. In other words, you can’t say vir virtūtis – you need to describe the virtūs in some way.

Genitive with Adjectives

The genitive case appears with certain Latin adjectives. We do something similar in English when we say “full of water” or “mindful of the truth”.

via est plēna aquae = the road is full of water

Sum memor fūtūrī = I am mindful of the future

There are many adjectives that take the genitive in Latin. Whenever you learn a new adjective, make sure you note down any specific cases that accompany it. This will make your life much easier.

Allen & Greenough’s says that the genitive is used after adjectives “denoting desire, knowledge, memory, fullness, power, sharing, guilt, and their opposites” (§349a). While it is helpful to realize that there is a thematic connection, don’t worry too much about these details.

Instead, my advice is that you simply remain aware of the fact that the genitive can depend on adjectives. That way if you come across a genitive with an adjective in the wild, you will have an idea how to proceed.

Here are a few adjectives that take the genitive:

- plēnus, a, um (+ genitive) = full (of)

- expers, expertis (+ genitive) = devoid (of), free (from)

- avidus, a, um (+ genitive) = desirous (of), greedy (for)

- cupidus, a, um (+ genitive) = desirous (of), eager (for)

- memor, memoris (+ genitive) = mindful (of)

- perītus, a, um (+ genitive) = skilled (in)

- potēns, potentis (+ genitive) = powerful (over), in charge (of)

This is by no means an exhaustive list, but it gives you an idea of what to expect. Note that some of these adjectives can also be followed by other cases.

Genitive with Verbs

The last use of the genitive that I will cover in this post is the genitive with verbs. Just like some adjectives can take the genitive, some verbs can, as well. Examples:

suae fīliae non oblītus est = he did not forget his daughter

mē damnāvērunt furtī = they convicted me of theft

Typically, verbs with the genitive fall into a few categories:

- verbs of remembering, forgetting, and reminding

- verbs of accusing, condemning, and acquitting

- and verbs of feeling, which include highly idiomatic impersonal verbs (e.g. paenitet, pudet, piget, etc.)

Just as I said above with relation to adjectives, don’t worry too much about memorizing all these details. As you read more and more Latin, you will naturally begin to pick up on which verbs require the genitive and which do not.

The most important thing is to be aware that this construction exists.

Final Thoughts on the Latin Genitive

How are you feeling? That was a lot of information. The genitive can express so many different nuances – it is truly a versatile case.

What’s more, this post does not even include every possible use of the genitive. Why? Because, frankly, you can take classification too far. Grammarians can keep splitting hairs about specific types of genitive, but some of these uses don’t even matter to me – and I’m almost done with my PhD in Classical Philology.

I’m here to give you the practical information you need to learn and read Latin successfully. But if you are interested in the intricacies of grammatical analysis, then check out these two resources:

- Allen and Greenough’s New Latin Grammar (available on Bookshop and Amazon)

- E. C. Woodcock’s New Latin Syntax (available on Bookshop and Amazon)

Allen and Greenough’s is the most comprehensive Latin grammar in the English language. It is full of useful paradigms and examples. Woodcock’s, on the other hand, offers a fascinating analysis of why Latin grammar works the way it does.

I highly recommend both resources to dedicated students of Latin. But beware – these books can be overwhelming for beginners. It might be best to wait until you are a bit more familiar with Latin!

MORE ON LATIN CASES:

You’re a lifesaver, this is so helpful! Thank you 🙂

So glad to hear it, Lucy! Good luck with your Latin!

What is the difference, if there is any, between the genitive case and the genitive singular used in determining a noun’s declension?

Hi Sam, this is a good question. The genitive case, like all Latin cases, can be either singular or plural. For example, *equī* is the genitive singular of *equus* (horse) and means “the horse’s / of the horse.” *Equōrum* is the genitive plural and means “the horses’ / of the horses.”

The genitive singular is consequently the same as the genitive case – but it is a specific “version” of the case, you might say, since the genitive can also be plural. I hope this helps!

Thank you so much for sharing your knowledge. I never realized that ‘Ecce homo’ was nominative…!

You are welcome, Paulo! Yes, it’s an unusual expression!