Latin Cases Explained: A Beginner-Friendly Introduction

Cases are a critical part of Latin grammar, but they can be confusing for beginners. This post explains all the Latin cases and their uses – with examples.

This post has two main goals. You will learn

- what the Latin cases are

- how to use them

Each case has a lot of different functions, and if I listed all of them this post would never end. Neither of us wants that! So here I will focus on the most important uses of each case.

I will focus on what you need to know now, as you are beginning to explore Latin. Simple and to the point – no confusing jargon or grammatical hair-splitting.

I also link to my posts on each specific Latin case, where you can find more information, explanations, and examples.

Let’s get started with an essential preliminary question: What are cases, anyway?

This post may contain affiliate links and I may receive a commission, at no extra cost to you, if you make a purchase through a link. See my disclosures for more details.

What are cases?

Cases are different forms that a noun, an adjective, or a pronoun can take. In this post, for the sake of simplicity, we will focus on nouns. But you can apply all of these principles to adjectives and pronouns, too.

(If you can’t remember what nouns, adjectives, and pronouns are, then check out Grammarly’s post on parts of speech.)

I said that cases are different forms of a noun. In Latin (and in many other languages) nouns change their endings based on their role in a sentence. These different endings signal different cases.

In other words, nouns have multiple possible endings, and each ending correlates to a case. That’s why we call such endings case endings.

The following chart shows the case endings for first declension Latin nouns.

(Click here for a full list of Latin noun endings.)

| Case | SINGULAR | PLURAL |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | a | ae |

| Genitive | ae | ārum |

| Dative | ae | īs |

| Accusative | am | ās |

| Ablative | ā | īs |

You attach these endings to each noun’s stem or base. So, for instance, the noun terra “earth” declined would be: terra, terrae, terrae, terram, terrā; terrae, terrārum, terrīs, terrās, terrīs.

English used to have case endings, but they have mostly disappeared. Our surviving cases are mostly in pronouns.

he = nominative / subjective

his = genitive / possessive

him = objective

You say “he sees the cat”, but “the cat sees him.” English speakers instinctively know that “the cat sees he” is wrong.

Why? It’s not the right case.

In Latin, the case system is highly developed. But the principle is the same as “he”, “his”, and “him.”

What are the cases in Latin?

Latin has 6 commonly used cases and the vestiges of a 7th.

The 6 primary cases are as follows:

Nominative

Genitive

Dative

Accusative

Ablative

Vocative

The vocative case is identical to the nominative, except for 2nd declension masculine nouns. For this reason, the vocative is not usually included in declension paradigms.

The 7th case is the locative, which only appears in very specific contexts and with certain nouns. Beginning students don’t need to worry much about the locative, but I will cover it briefly at the end of this post.

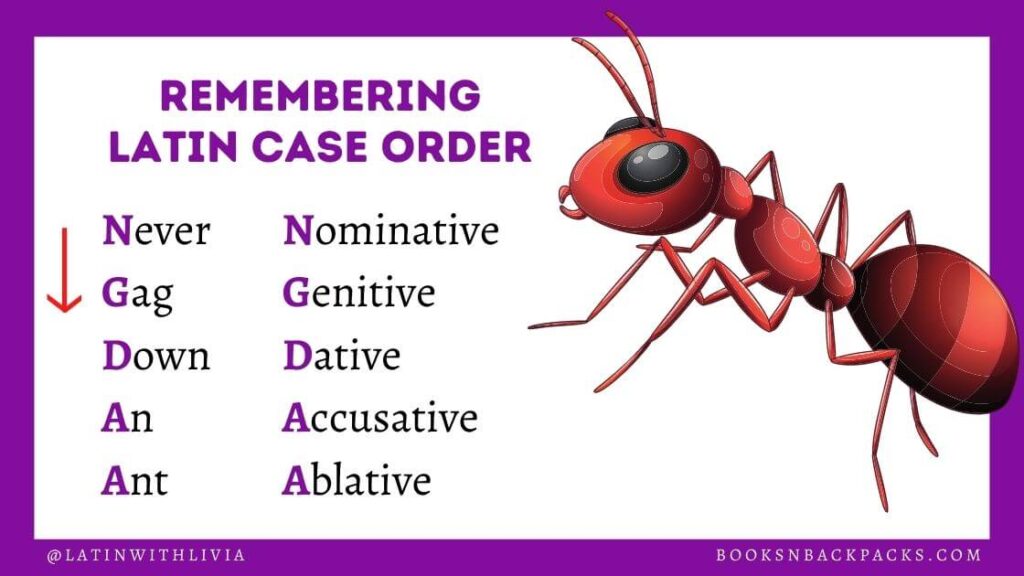

In the United States, the Latin cases are usually listed in the exact order that I have given. Here is a mnemonic to help remember the order of Latin cases:

Never gag down an ant.

The first letter of each word is the first letter of one of the cases. My Latin students at Harvard supplemented this sentence to include the vocative:

Never gag down an ant violently.

I specify that this is the order of the Latin cases in the United States, because this order is not universal. In many parts of Europe, cases are listed in the following order: Nominative, Accusative, Genitive, Dative, Ablative.

On this website, I use the U.S. version. This is partly because this was the way I was taught, but mostly because I think it makes more sense. The genitive case is crucial for so many reasons, so it deserves to come second.

So there you go. Now you know what the Latin cases are and what order to list them in. Time to talk about their uses!

Uses of Latin Cases

Nominative Case in Latin

The nominative is the default case in Latin. This is the form that you will see listed first in your textbook or dictionary.

There are two main uses of the nominative: 1) subject and 2) predicate nominative.

First, the nominative is used to indicate the subject of a sentence. Remember: the subject is the one who performs the action of the main verb.

The girl sings. = Puella cantat.

In this sentence, the girl is the one performing the action of singing. So we put puella (girl) in the nominative case.

A predicate noun is also in the nominative case. This sounds fancy, but all it really means is that if you say something is equal to something else, that second something is also in the nominative.

Claudia is a girl. = Claudia est puella.

What’s happening here? Well, Claudia is the subject, and puella (girl) is the predicate nominative. Since Claudia is nominative as the subject, it makes sense that puella would be nominative, too, since Claudia = puella.

👉 Click here for more information about the nominative case.

Genitive Case in Latin

The genitive case is crucial in Latin. You need to know a noun’s genitive in order to determine what declension it belongs to and to find its stem.

For this reason, textbooks and dictionaries will list the genitive after the nominative. This is also why you should always include the genitive singular when you are making your Latin flashcards.

There are many uses of the genitive, but I want to highlight the most important one here. The classic use of the genitive is to show possession.

liber puellae = the girl’s book / the book of the girl

spēs amīcōrum = the friends’ hope / the hope of the friends

Other important uses of the genitive include the partitive genitive and the objective genitive. Pro tip: you can typically translate the genitive as “of [blank]”.

👉 Click here for more details about the genitive case.

Dative Case in Latin

The dative case has many uses, but here we will look at its most characteristic one: the dative of indirect object.

The indirect object is the person (or sometimes thing) indirectly affected by the action of the verb. Look at the following examples:

Canem puellae dant. = They give a dog to the girl.

Multa amīcīs dīxī. = I said many things to the friends.

Other important uses of the dative include the dative of reference, dative of possession, and dative with special verbs. Pro tip: most of the time, you can translate a noun in the dative as “to / for [blank].”

👉 Read this post for a more detailed account of the dative case.

Accusative Case in Latin

The accusative is the case of the direct object (among other things). The direct object is the person or thing that receives the action of the main verb.

Here are a few examples:

Puellam videō. = I see a girl.

Saxum portās. = You carry a rock.

In the first sentence, the girl receives the action of seeing. In the second, the rock receives the action of carrying. Thus both puellam and saxum are direct objects and must be in the accusative.

Other important uses of the accusative include place to which, extent of space or time, and subject of an indirect statement.

👉 Read this post for more about the accusative case.

Ablative Case in Latin

The ablative case is the “everything” case, so it is hard to summarize its uses quickly. Here I will discuss two basic uses: the ablative of means and the ablative after prepositions.

The ablative of means is used to express the object by means of which you do something. You can translate this type of ablative as “by / with [blank]”.

Litterās stilō scrībō. = I write a letter with / by means of a pen.

Canem aquā lavō.= I wash the dog with / by means of water.

Note that you do not need a preposition in Latin to express “with” like you do in English. The simple ablative is enough to express means.

Another use of the ablative that beginning students will meet quickly is the ablative after prepositions. We can further divide this type into the ablative of place where, ablative of accompaniment, etc.

Basically, some Latin prepositions take the ablative. Here are some example sentences:

Cūr clāmās in silvīs? = Why are you shouting in the woods?

Sine mē fuistī. = You went without me.

Omnia prō Rōmā fēcērunt. = They did everything for Rome.

Other common uses of the ablative include the ablative absolute, the ablative of manner, and the ablative of agent.

👉 For more details about the ablative, read this post.

Vocative Case in Latin

The vocative is used for direct address. When you speak to someone and use their name, that name is in the vocative.

For most Latin nouns, the vocative looks identical to the nominative, but the second declension preserves distinct case forms.

Marce, mēcum venī! = Marcus, come with me!

Cūr nōn audīs, soror? = Why aren’t you listening, sister?

👉 Click here for more examples and details about the vocative.

Locative Case in Latin

The locative case is only partially present in classical Latin. Why? Because the ablative case has stolen its usage.

The locative expresses the place where something occurs. But – thanks to the ablative’s incursions – the locative only exists for the names of cities, small islands, and a few random words (domus and rūs).

Rōmae sunt multī cīvēs. = There are many citizens at / in Rome.

Esne domī? = Are you at home?

👉 Want a more detailed account of the locative and where it still exists? This post will help you out.

Latin Cases: A Summary

By now you should understand what Latin cases are and have a basic idea of their use. If things still seem fuzzy, don’t worry. It takes time, but if you persevere, cases will become second nature to you.

I have emphasized throughout this post that most Latin cases have multiple uses, and I have linked to posts with more in-depth treatments of each case. But here is a brief summary of the most characteristic uses of each case:

- Nominative: subject

- Genitive: possession (of [blank])

- Dative: indirect object (to/for [blank])

- Accusative: direct object

- Ablative: means and prepositions (by/with/from/in [blank])

- Vocative: direct address (O [blank])

- Locative: location (in/at [blank])

As you continue studying Latin, you may find the following posts helpful:

My Favorite Latin-Learning Resources (Free & Paid)

Best Latin Dictionaries for Students

Well done! Very helpful.

I’m glad the post was helpful, Ted!

so helpful!! thanks so much

You are welcome, Lima!

Best explanation of Latin cases I could find – thank you 🙂 Would be good to have exercises with english translation for practice.

You are welcome, AJ! Hopefully in the future I can add exercises!

This is very well laid out and easy to use…. fantastic job. I am relearning Latin after 30+ years after my Jesuit education, and this is a great resource. You are very good at this. Thank you!!

You are welcome, Anthony! Good luck with your Latin studies 🙂

I am using “Homo sapiens prōlixus” in a novel to indicate the next step in human evolution: wise, long-lived human. Am I correct or incorrect?

Hi Paul, I think that this works well! Good luck with your novel!

Thanks for everything you are doing. Your site is a life saver. It simplifies things a lot.

You are welcome, Amine! I’m glad my site is helping you out!

Trying to understand how to distinguish declensions:

If you have the same ending on a given noun, like aqua or aquae, it can be seen as either nominative singular/ablative singular for ‘aqua’, or genitive singular/dative singular/nominative plural for ‘aquae’. How can you tell the difference if the word is not in the context of a sentence.

Similar question:

When you have two nouns or a noun and an adjective together that do not match in ending, how do you tell which takes priority? For example, how would one translate ‘terra mariae’?

Hi Luke, great questions. The answer to your first question is that, without context, you *can’t* tell what case an ambiguous form like *aquae* is in. It’s kind of like in English how you wouldn’t know if the word “lead” is a noun or a verb if you saw it in isolation.

Now for your second question. First of all, an adjective ALWAYS has to agree with its noun, so if an adjective and noun don’t have the same case, number, and gender, this means the adjective is not modifying that particular noun.

If you have two nouns together, you have to figure out what relationship the different cases are establishing between the two nouns. In your example, *terra Mariae* has a nominative (terra) and a genitive (Mariae) and so it means “the land of Maria” or “Maria’s land.”